I did a lot of drugs in my youth. Started drinking at 14 or so, became a daily pot smoker at 17, and tried ecstasy, acid, mushrooms, and ketamine before I left high school. A couple years after that, cocaine became my thing. My habit never got to the point that I needed rehab, although I basically moved out of Boston to get away from my cocaine.

One reason my drug habit never escalated into dangerous territory was because I had a “no heroin” rule, and I’m pretty sure that’s because of all the movies I watched in the 1990s. As heroin spread from the cities to the suburbs, the movie began to reflect its infiltration into mainstream (read: white middle-class) society. Trainspotting, Requiem for a Dream, The Basketball Diaries, Killing Zoe, Basquiat, Traffic, even Pulp Fiction. Although the source material for some of these films comes from the ‘80s, it took the indie film movement of the ‘90s for them to flourish, and the impact on young American lives was immeasurable. These films delight in the allure of drug use before demonstrating the awful underbelly. They show in no uncertain terms how heroin will ruin your life.

I liked drugs, but I didn’t want my life ruined. If my memory is accurate (and there’s a strong chance it’s not), I was offered heroin just once, and I turned it down. I didn’t want to end up like Jerry Stahl, the author of Permanent Midnight, a memoir adapted for film and released in the fall of 1998, when I was fresh out of high school and ready to ingest almost anything put in front of me. In real life, Stahl was a promising young writer and nascent addict who took a job in Hollywood writing for the sitcom ALF, sunk deeper into his self-loathing, and became a full-blown junkie. The film chronicles his descent into addiction, the dissolution of his marriage to his producer wife (Elizabeth Hurley), the chances he blew, the rock bottoms he hit, and finally, his first steps out of hell.

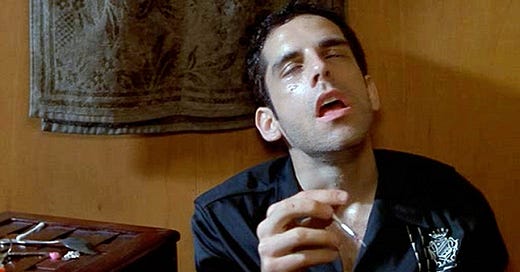

As a film, it has a few problems, particularly its clunky framing device that finds Stahl shacked up in a motel room with a horny narcissist’s dream, an underwritten and impossibly adorable woman (Maria Bello) who wants to do nothing but screw and listen to his story. Flaws aside, the film succeeds largely on the back of Ben Stiller, who gives one of the most raw, vulnerable performances of his career. It was a huge step out of his comfort zone, as Stiller had mostly done comedy at this point in his career (the dark, acerbic Your Friends and Neighbors came out the same year). To be sure, there are moments of dark comedy in Permanent Midnight, but there’s also just plain darkness, and one of the great achievements of Stiller’s performance is how he holds the film’s razor-wire tone.

As Stahl begins to spiral out, his mania is both acutely disturbing and deeply hilarious. His writers-room rant—in which he name-drops Fritz Lang, Patty Duke, and Ethel Merman—borders on the virtuosic. Stiller uses all his physical and intellectual comic chops, while playing the physical derangement of the drug and a total lack of self-awareness. There’s no evidence Stiller has any personal experience with heroin (he relied heavily on the advice of the real-life Stahl, who was present throughout filming) but I wonder if he drew on a lifetime spent as the progeny of two showbiz legends to find this distinct blend of crowd-pleasing desperation.

Still, if Permanent Midnight kept me away from heroin, it wasn’t the film’s black humor. That was the sugar sprinkled on top of the poison. The casual sex and petty crime in Trainspotting, dancing with Uma in Pulp Fiction, or Blinkie and Winkie in The Basketball Diaries. It’s the sexy side of habitual drug use that these films use to lure you in before pulling out the rug. It’s impossible to pinpoint when Jerry’s life turns scary—although the scene where he smokes crack and throws himself against the window of a skyscraper just for the rush comes close—because the film purposefully takes the motivations behind his addiction for granted. Why does he do heroin? Because he’s an addict. His descent is inevitable. It’s this refusal to moralize or psychoanalyze addiction that separates the heroin films of the ‘90s from the after-school specials of the “Just Say No” era. There are key moments along the way, like when his mom dies, he gets fired from the sitcom (twice), and his wife becomes pregnant. The fact that each of these disparate events send him to a new level of depravity underlines the propulsive nature of his addiction: any life event, good or bad, is a reason to shoot up.

I’ve seen all the heroin movies but this is the only one that makes you feel what heroin feels like. I could take or leave the hallucination in which “Mr. Chompers” (a stand-in for ALF) tries to break through the bathroom door while he’s shooting up. Scenes like that are designed for the trailer. I was more impressed with how Stiller physically manifests the impact of the drug, the way he crosses his eyes, slurs his speech, and breathes as if he has a paper towel over his mouth. I’ve seen all of this before, but he simply does it better than anyone else. Most actors just mumble and crawl through their drugged-out performances. Stiller shows where the ecstasy and the agony collide.

It’s cringe comedy of the highest order that eventually transforms into pure cringe. Maybe this was the real deterrent. My main fear as a teenager wasn’t throwing my life away. I still saw some poetry in addiction, probably because all my artistic heroes had struggled with drugs and alcohol. Some of them died from it. But there’s nothing cool about embarrassing yourself in front of your friends and colleagues, and becoming so pathetic that Elizabeth Hurley doesn’t want you around anymore. That’s the shit that stays with you forever, or at least I thought it did as a teenager. Other drug movies don’t get into shame because their protagonists quickly end up on the street or close to it. They have nothing to lose. Jerry Stahl has made it to the top of the mountain, so he has everything to lose. As a young, upper-class teenager, so did I. Permanent Midnight might have shamed me into saving my own life.

I love this, Noah. I vividly remember watching this film on VHS when I was 20 or 21 and being transfixed. It was one of the first excruciating drug-addiction movies I ever saw, maybe even before Trainspotting or Requiem, and it put me through the wringer. Stiller shows so much range and darkness, as you eloquently described. Well written, my friend!